When baseball remained king, all of us wanted to be him

We wanted to be Pete Rose.

We might have wanted to be Joe Washington, Roger Staubach, Reggie Jackson and Dr. J, too, but mostly we wanted to be Rose.

It was before Larry and Magic came along to save the NBA. Before the NFL had taken over the world. Before all that baseball free agency would bring had been wrought.

We knew Perez, Morgan, Rose, Concepcion, Griffey, Geronimo, Foster and Bench comprised the Big Red Machine.

We knew Garvey, Lopes, Russell and Cey manned the Dodger infield.

We didn’t know a whole lot about the Cleveland Indians, the Chicago White Sox or even, unless we listened to them on the radio, the Texas Rangers.

They were never on TV.

But we knew Reggie and Catfish Hunter, who’d been A’s and would controversially become Yankees thanks to their still new big spending owner, name of Steinbrenner.

We knew Henry Aaron remained in the game, but had left Atlanta for Milwaukee, returning to the city in which he’d previously played as a Brave.

We knew Nolan Ryan had thrown no-hitters, Yaz was in Boston and Rod Carew, in Minnesota, could flat hit.

We actually knew a fair bit more than that, because we collected the cards of the players who, in our 7-, 8-, 9- and 10-year-old heads, played the most important sport in the world.

We were right about that, of course.

Rose, who was famously caught betting on baseball, who agreed to his banishment from the game likely in fear of investigations into him continuing if he didn’t, who then denied he’d ever gambled on the game anyway, who after years and years of denials finally admitted he’d done it, died on Monday.

He was 83.

And that’s where my mind goes.

We wanted to be him.

I think I became a Reds fan because my father was a Reds fan because Johnny Bench was born in Oklahoma City and grew up in Binger and was the greatest catcher the game’s ever seen.

But Rose eclipsed Bench.

Not as a ballplayer.

Bench played the more important position, Rose played every position but shortstop. Bench hit for power, Rose mostly didn’t. Bench impacted the game defensively more than any catcher and maybe any player, period, Rose was almost a utility player, but he could hit, run the bases and refuse to accept the defeat like the dickens.

Rose eclipsed Bench and everybody else as a presence, a leader and practitioner of the game that made your jaw drop and your butt come out of your seat.

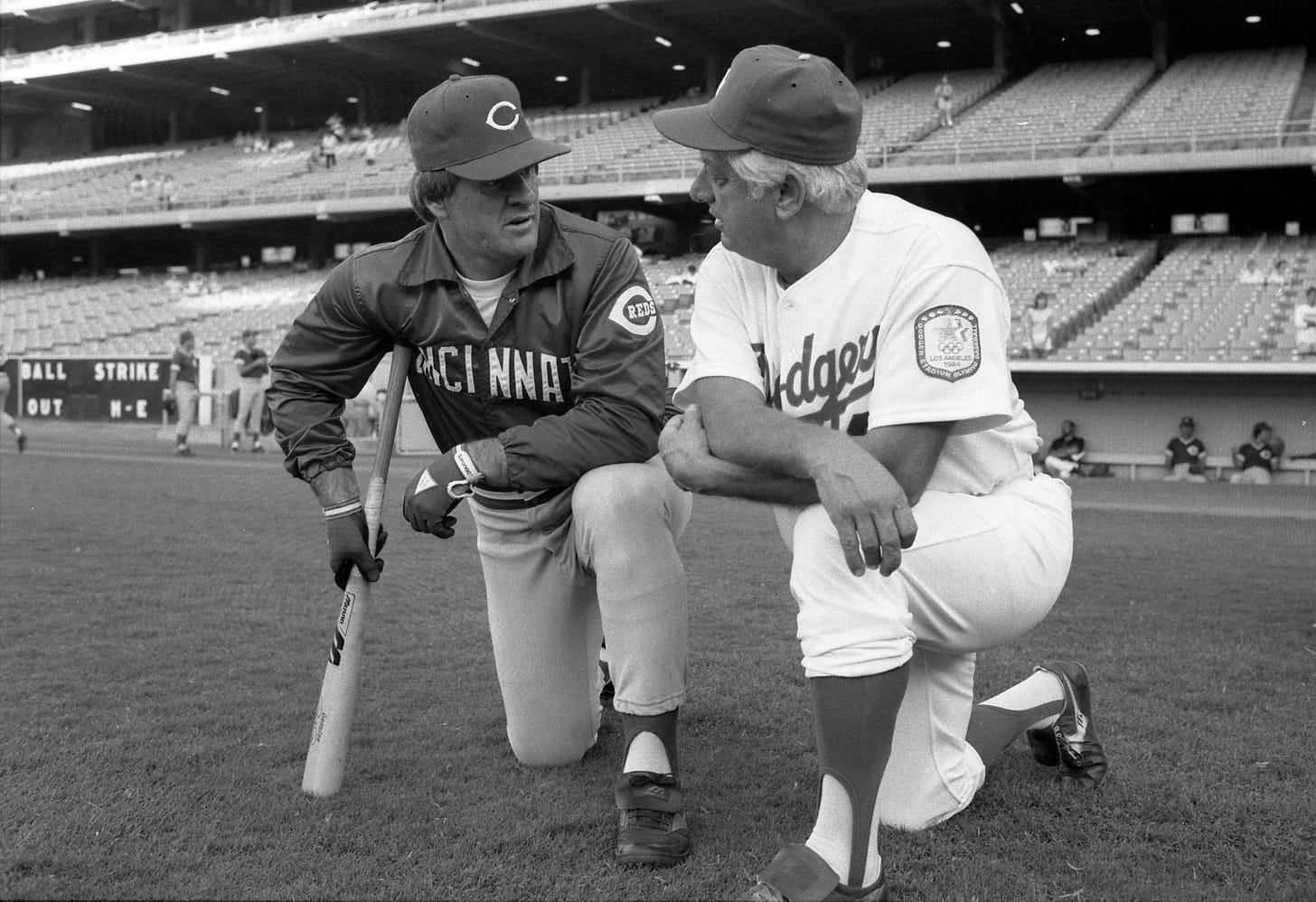

See that picture up there?

That’s Rose sliding into third base, only he did not really slide into third base, because slides take place on the ground.

Rose took flight, the toes of his spikes rising higher than his head as he went first to third on a teammate’s single, stretched doubles into triples or stole the base.

If you’re not of a certain age, you can’t remember a time you couldn’t watch baseball every day of the week.

You don’t remember the revolution that was cable television, the Braves playing on WTCG, channel 17, out of Atlanta, soon to become WTBS, and the Chicago Cubs playing on WGN, always in the afternoon if they were home, for Wrigley Field had yet to add lights, meaning there were days you came home from school, turned on the TV and there was a baseball game on and it was unthinkably glorious.

Before, there was just the Game of the Week on Saturday afternoon and, for a while, Monday Night Baseball, Howard Cosell, among others, on the call.

But for the ALCS, the NLCS and the World Series, that was it.

Still, even in a sport your heroes step to the plate just four or five times a game and fail to reach base two-thirds of the time, everybody knew Rose, the passion with which he played, that his nickname was Charlie Hustle, that they were watching something absolutely singular.

I’m trying to think who played their sport the way Rose played his and it’s not an easy thing to do.

Maybe Larry Bird played basketball the way Rose played baseball. Maybe Gordie Howe or Mark Messier played hockey the way Rose played baseball. Maybe Jim Brown or Walter Payton played football the way Rose played baseball.

Wait, I’ve got it.

Jimmy Connors played tennis the way Rose played baseball and very nearly had the same haircut, too.

If you know, you know.

Though he accumulated so many, Rose played in a way that belied statistics, that reflected heart, soul and will rather than terrific talent or artistry, that wowed you with effort for which there weren’t words.

We wanted to be him but we couldn’t be him.

I could never bat left handed as well as I could bat right handed and I could never go head first into third base.

I was afraid.

Timmy Ellis, Linwood Lion catcher, who grew up on 16th Street, two blocks down from me on 18th, was not afraid, but the rest of us were.

Stealing from the greatest living sportswriter, Joe Posnanski, who was out with his Rose column Monday night …

The numbers are staggering. Games played: 3,562. Record. Plate appearances: 15,890. Record. Times on base: 5,929. Record. And, most of all, there are all those hits, 4,256 of them, a numerical marvel.

The first half of the hit total, 42, is Jackie Robinson’s uniform number.

The second half of the hit total, 56, is Joe DiMaggio’s unbeatable hit streak.

Also, Rose played no less than 160 games 10 different seasons, in all 162 games six different seasons and two other seasons, somehow, managed to play 163. Unbelievably, he holds both the 12th longest consecutive games played streak in major league history (745) and the 16th (678).

He still claims the longest hitting streak in NL history at 44 games, compiled 10 different 200-hit seasons and, in one, 1973, finished with 230

All that and in his 23rd big league season, as Reds player-manager, following five seasons as a Philly and most of one as an Expo, though his batting average was .264, 39 points off his lifetime .303, his on-base percentage was .395, 20 points higher than his lifetime .375.

That is, at 44, he remained an effective player.

It was also that season, on Sept. 11, 1985, he broke Ty Cobb’s all-time hit record of Padre pitcher Eric Show, or as ESPN’s Chris Berman called him, Eric “Win, Place or” Show.

Rose even went 412-373 as Reds manager.

Still, mostly, we wanted to be him, because nobody played the game so undeniably and 1970s baseball was the greatest thing.

Ask any of us.