Remembering Terry Funk, a king of the ring

I knew Terry Funk.

I’d never seen him wrestle, never seen him on television, not even on the mic, but I knew who he was.

I bought the magazines at Taylor’s Newsstand in downtown Oklahoma City.

I got a book called “Main Event” for Christmas one year, Bob Backland and Superstar Billy Graham on the cover.

I might have been 12.

Backland was the World Wide Wrestling Federation champion, having topped Graham for the crown. Nick Bockwinkle and Verne Gagne were trading the American Wrestling Association belt back and forth. And Harley Race owned the National Wrestling Alliance’s title.

It was a big day for me when the magazines decided to quit calling the WWWF belt a world title, the reasoning being it was pretty much confined to the upper northeast and thus a regional championship, exactly what I’d been thinking for a year or two at least.*

*Even if it eventually became the last promotion standing, morphing into the WWF and WWE, killing the squared circle as we knew it.

The NWA title was defended coast to coast, in associated “territories” from the Pacific Northwest to Florida, not to mention the Carribean, Japan, New Zealand and Australia — now that’s a world title! — and the AWA stretched through much of the Midwest and into Canada, covering real ground, so close enough.

I digress.

I knew Funk because he was in the mags, in the book and forever prominent because he was once NWA champ, from Dec. 10, 1975, when he took the belt from Oklahoma State’s own Jack Brisco, who’d carried it most of three years, in Toyohashi, Japan, before dropping it to Harley Race, in Miami Beach, on Feb. 6, 1977.

I didn’t know the locations and dates then, of course, but I kind of knew the years and surely knew the names. By some point in middle school, I’d memorized the NWA, AWA and WWF title histories.

Seriously.

Eventually, I saw him.

I must have seen him in Georgia, I might have seen him in Kansas City, I don’t think I ever saw him in World Class, Fritz Von Erich’s DFW Metroplex promotion, but I entirely remember him in WCW — World Championship Wrestling — what the Georgia promotion later became.

Here’s what I remember.

When Terry Funk arrived, it was about to get real. And, now that I think about it, what better measure of pro wrestling greatness is there?

Do they make you believe it?

Do they not merely suspend your disbelief as you watch them, but keep it suspended until you watch them again?

Funk did that.

His brother, Dory Funk Jr., preceded him as NWA champ, taking it from Gene Kiniski in February of ’69 and surrendering it to Race in May of ’73, who two months later dropped it to Brisco.

Dory was often referenced as “the greatest technical wrestler” going, him or the AWA’s Billy Robinson. Terry had those skills, too, but all things being equal, would just assume brawl.

And yes, as I write this, I see I’m treating it as a competitive sport rather than predetermined, but how else to describe it? That’s what it felt like and Terry Funk was among its greatest practitioners.

Funk’s rise began in the territory run by his father, Dory Sr., called Western States Sports, headquartered in Amarillo and stretching from El Paso to the Oklahoma panhandle, but his intersection with most fans through the 80s occurred when he’d enter a territory as an outsider, wreak havoc for a period of weeks or months, before moving on to the next pasture.

He carried a branding iron.

He hailed from the “Double-Cross Ranch.”

He actually did.

275 acres near Canyon, Texas, south of Amarillo.

Much has been written about a three-match trilogy between Ric Flair and Ricky Steamboat, between February and May of 1989, the NWA world title at stake each time.

Steamboat claimed the first one, Feb. 20, in Chicago. Steamboat prevailed again in a best two-of-three-falls contest that dang near went an hour inside the Superdome on April 2. The last took place on May 7 in Nashville with a special stipulation: if it went the time limit, a panel of three former NWA champion judges would settle things.

The panel?

The great Lou Thesz, Pat O’Connor and, of course, Funk.

Flair won via a small cradle as Steamboat, his left leg weakened by Flair’s figure-four leglock, failed to finish a scoop slam.

Flair and Steamboat, who propelled each other to the top of the sport a decade earlier in the Carolinas actually shook hands. Flair then raised Steamboat’s hand. Deeply satisfying for a long-time fan like me, the work became a heart-warming shoot.

But in a blink, Funk was in the ring, tuxedo and all, stealing Flair’s spotlight and asking for a title shot.

Funk hadn’t been an active wrestler for a bit, had announced his retirement once or twice already, but when Flair didn’t give him the answer he wanted, he flipped out, beat him up, even piledrove him on table outside the ring that was probably supposed to break but didn’t.

Flair, though, survived — as the story went, he paid Funk’s $100,000 fine, thus lifting his suspension just to get him back in the ring — and their feud ran until Nov. 15 at the Superdome, when, in an “I Quit” match, Funk submitted to the figure four.

Eight years earlier, Funk had shown up in Memphis where, naturally, he feuded with Jerry Lawler, leading to a sort of “I quit” match.

They met inside an empty 11,300 seat Mid-South Coliseum, Funk having challenged Lawler to the stipulation, claiming everybody to be on Lawler’s side: fans, cops, referees, making an empty arena required.

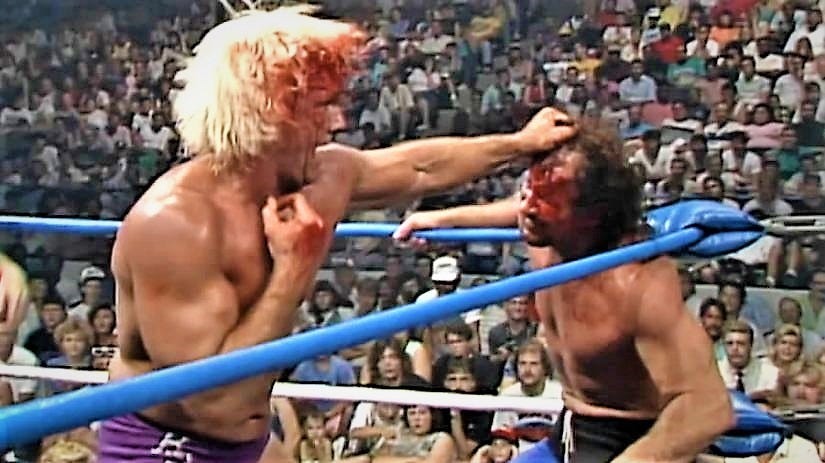

Funk wasn’t yet 40 for that one, was seven weeks short of his 45th birthday when he attacked Flair and in his middle 50s when he showed up in ECW — Extreme Championship Wrestling — where, never afraid to bleed buckets, he fit right in.

He wound up specializing in those kinds of matches for another decade-plus: exploding rings, barbed-wire affairs — wrestling porn — all over the world.

There are pictures and videos and they’re insane and he did it for years, putting his body through such ridiculousness over the third iteration of his career.

His last match?

It came in 2017, in Spartanburg, S.C., 42 years after it all began in Amarillo, a six-man tag: Funk and the Rock’n’Roll Express — Ricky Morton and Robert Gibson, still at it after all these years — against Lawler, Brian Christopher and Doug Gilbert.

He was 73.

I didn’t care for his last decade or two in the ring.

He was never not tougher than nails, even as he helped wrestling become a live slasher movie. It was a movement that set wrestling back, the response to which has been a brand of wrestling so the opposite, so choreographed, so clean, scripted and family friendly, I can’t watch it either.

Still, Funk was a king of the ring.

He did it forever. His impact was real.

In top form, he made it real, too.

Like few before, and nobody since.

He died on Wednesday.

He was 79.